More than 50 years ago, two men climbed into a massive, blimp-like submersible, descended about 35,800 feet (10,912 meters) to the deepest point in the ocean, and became the first people to observe the dark underworld of one of Earth’s most extreme environments. No one had been back since, until March 26, 2012, when James Cameron, a National Geographic explorer-in-residence, made a record-breaking solo dive to the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench in a custom-built submersible that he co-designed.

Although best known for directing films such as Titanic and Avatar, Cameron is an avid explorer with 72 submersible dives to his credit—51 of which were in Russian Mir submersibles to depths of up to 16,000 feet (4,877 meters), including 33 to Titanic.

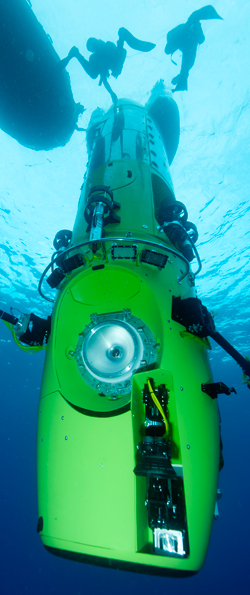

For this expedition, Cameron squeezed into a pilot sphere so small he could not extend his arms. He was the sole occupant in a complex, 24-foot-long (7.3-meter-long) craft made primarily of highly specialized glass foam. As he maneuvered on the ocean floor amid unexplored terrain and strange new animals, Cameron filmed footage for a feature-length documentary and collected samples for historic research. Why? To promote exploration and scientific discovery.

The dive was part of the DEEPSEA CHALLENGE expedition, a partnership with National Geographic that took Cameron, along with fellow pilot Ron Allum and a team of engineers, scientists, educators, and journalists, to the greatest depths of the ocean—places where sunlight doesn’t penetrate and pressure can be a thousand times what we experience on land. After years of preparation, the team went to the Mariana Trench, a 1,500-mile-long (2,400-kilometer-long) scar at the bottom of the western Pacific Ocean. There, about 200 miles (320 kilometers) from Guam, Cameron continued the work that Don Walsh and Jacques Piccard, the first men to dive the trench in the bathyscaphe Trieste, started in 1960. While the Trieste was not equipped to take pictures or get samples, Cameron and his DEEPSEA CHALLENGER submersible were armed with multiple cameras and a mechanical arm for scooping up rocks and animals. These samples could enable groundbreaking discoveries: Studying the forces that shape these trenches could help us to better understand the earthquakes that cause devastating tsunamis; studying the fauna that survives there could lead to breakthroughs in biotechnology and our understanding of how life began.

For Cameron, who explored the Titanic wreck during his production of the Academy Award-winning film, reaching the deepest point on Earth was a long-term goal. “Imagination feeds exploration,” he says. “You have to imagine the possible before you can go and do it.”