Postdive Truths Revealed

Jacquinot Bay, New Britain Island, Papua New Guinea

The first 24-hour period after Jim’s 7-hour dive to 12,000 feet (3,658 meters) is filled with intensive debriefing sessions in which the technical and operational truths of the dive are revealed.

Here are some of them.

The task loading on the pilot of the DEEPSEA CHALLENGER is extreme. Jammed into a space not much bigger than the trunk of a Prius, he makes 50 decisions a minute about the status of his depth, speed, direction through the water, power supply, oxygen supply, temperature, thrusters, cameras, recorders, and lights. He uses seven joysticks to control the various functions of the sub at the same time he’s trying to communicate his status to the communications team on the mother ship. He’s moving the sub in three dimensions so he’s thinking in three dimensions. He’s a warp-speed chess player, anticipating every next move.

When Jim was in position in front of the lander Mike, he felt a sudden current shift the 12-ton sub. Not far away is the narrow passage between the big islands of New Britain and New Ireland. Each day, driven by the tide, enormous volumes of water flow from the Bismarck Sea to the Solomon Sea and back again. There may, or there may not be, a connection between this tidal flow and the sudden current at 12,000 feet (3,658 meters). This part of the ocean has never been systematically studied so, for now, the source of the current is a mystery.

Six and a half hours into the dive, the voltage dropped in two sections of the battery array and tripped the trim shot release. Most of the trim shot dropped out of the hopper and, without warning, the sub started up from the bottom. “It was a spontaneous ascent at a speed of one knot,” Jim tells us. “I still had the main ascent weights so it wasn’t as serious as it might have been.” Jim and the team spent a long time discussing the anatomy of the problem and how to improve the sub’s power management system so it won’t happen again.

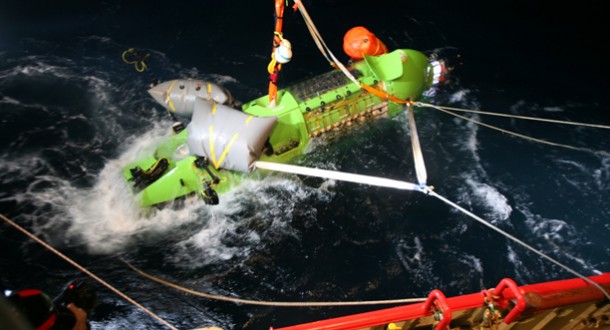

When the DEEPSEA CHALLENGER arrived on the surface at midnight last night, waves were coming from one direction, swells from another, and the wind from another. Looking over the starboard side of the ship, we saw the Kawasaki-green sail of the sub, bathed in lights from the ship, rise and fall and rise again. Rich ran the inflatable next to the sail and dropped the divers. In a splendid display of seamanship, Captain Stuart Buckle used full power on his bow and stern thrusters and main engines to bring the ship in close so a diver could reach up, grab the crane hook, and attach it to the top of the sub. Even with the lift wire and tag lines attached it was hard to keep the sub from jerking up and down. “I felt one bang, another, and then a big jolt,” Jim tells us later. As the 24-foot-long (7-meter-long) sub came over the bulwark, a big swell ran under her and she began to swing. David Wotherspoon barked out some orders, tag lines went taut, and the sub shuddered to a stop. When the four thick steel arms went up to lock the sub into her cradle, everyone started breathing again.

A seven-hour dive to a depth of 12,000 feet (3,658 meters) is hard on any sub, and the two days following are routinely set aside for the sub team to prepare the vehicle for her next descent. In addition to a briefing, batteries are charged, life-support systems are replenished, and things that need fixing are repaired.

For everyone on the Mermaid Sapphire, these dives are a lot like spaceflight. We’re in a remote corner of the South Pacific and help is hundreds of miles away. If something goes wrong, we have to fix it, and fix it quick. There’s no such thing as waiting for the rescue team. We deal with it, or else. And all of these “or else’s” are not very appealing.

Photograph by John Bruno