Preparing a “Great Whale”

Jacquinot Bay, New Britain Island, Papua New Guinea

A sprawling gray raincloud moves in from the west and hangs over the bay for most of the afternoon. The intermittent rain—more like a Scottish mist than a tropical downpour—brings welcome relief from the sun and the heat. After the rain, slim ghosts of steam rise out of the dense green hills.

The sub team spends the day preparing the DEEPSEA CHALLENGER and lander Mike for tomorrow’s five-mile (eight-kilometer) dive. The sub’s altimeter and sonar need major adjustments, and lander Mike’s cameras have a serious stereo signal problem that has to be solved.

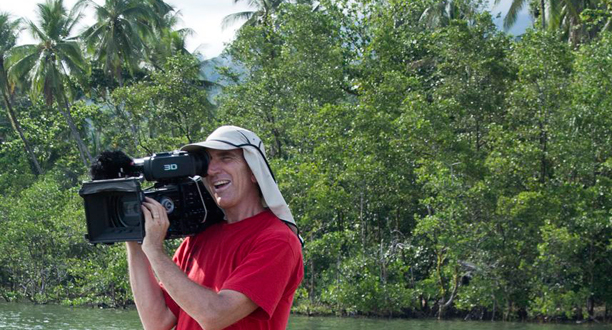

Glenn Singleman is the expedition’s medical doctor. An emergency care specialist from Sydney, Australia, he embodies the multi-skill-multi-task-any-time-day-or-night ethos at the heart of this project. Glenn is a veteran of Jim’s last two deep-sea expeditions. He’s a scuba diver, mountain climber, BASE jumper, and filmmaker. Within the space of an evening, he can clean and stitch together the deep wound in Sako Palagin’s forearm and tell hair-raising stories about the 1989 black-tie dinner party he and his mates had at 22,000 feet (6,700 meters) on the snow-covered slopes of Mount Huascaran in Peru. He’s also a film director and cameraman who has produced award-winning documentaries for National Geographic and the Australian Broadcasting Company. It’s no surprise that the man who flies through the air at 10,000 feet (3,000 meters) in his bat-wing “speed suit” is an expert on the subject of risk.

“When you work in a hospital emergency room,” he tells me, “you see patients with heart attacks, gunshot wounds, and strokes. Some nights you see all three at once. You have to make life-and-death decisions and make them fast. You learn how to think in a crisis. You learn how to maximize the use of life-saving technologies. To be effective, you create a mental rapid-response, risk-assessment system.

“On this project we’re exploring the most extreme environment on Earth. It’s an opportunity to participate in the physical and mental limits required to select and operate the technologies we need to dive miles under the ocean and do it safely. We’ve come this far because for months highly focused people like Jim have been thinking hard about the risks and the technologies needed to navigate around them.”

Later in the day Jim shares some of his thoughts about tomorrow’s five-mile (eight-kilometer) dive. “When we made our seven-hour dive to 3,700 feet,” he says, “we joined the exclusive deep-sea submersible club that includes Russia’s Mirs, France’s Nautile, China’s Sea Dragon, Japan’s Shinkai, and America’s Alvin. The difference is that our sub was built by an intense bunch of engineering geeks who thought they could invent a new kind of deep-science vehicle. That’s pretty cool. But we have to be realistic. Tomorrow we’re going much deeper and we’ll squeeze things a lot harder. Things may show up that we haven’t seen.”

The DEEPSEA CHALLENGER expedition is an epic struggle between the human mind and the power and unpredictability of nature. Whatever the outcome, we’ll come away much stronger and wiser. Herman Melville said it best: “I love all men who dive. Any fish can swim near the surface, but it takes a great whale to go downstairs five miles or more.”

Photograph by Charlie Arneson