The Checklist Guru

Ulithi

This morning we moved the Mermaid Sapphire a short distance inside the Ulithi lagoon until she was over the U.S.S. Mississinewa, an oil tanker that was torpedoed in 1944 and went to the bottom fully loaded. The wind had more strength than yesterday and a three-knot current was running. We dropped the ship’s remotely operated vehicle (ROV) over the side and spent an hour inspecting the 500-foot-long (152-meter-long) tanker lying upside down on the seafloor.

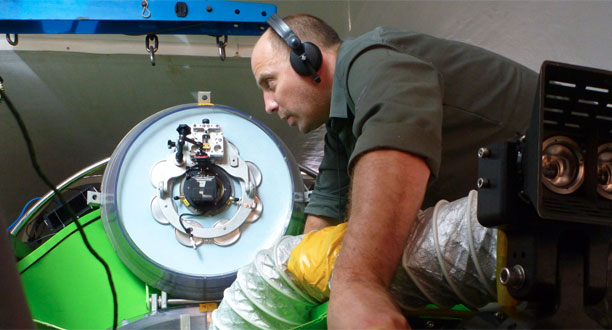

This afternoon I learned a new way to spell life support. J-o-h-n G-a-r-v-i-n. The six-foot-two John is the last person Jim sees before the hatch closes at the start of a dive and the first person he talks to when it’s opened eight hours later. John is the “checklist guru,” the man who makes sure the sub and her network of complex systems are ready to dive. During lunch he told me there was a short interval in the countdown for the next dive and asked if I would like to spend a few moments inside the pilot sphere.

Like so many people on Team Cameron, 41-year-old John has a resume that makes you wonder how one person can do so many interesting things in such a short time. He was an actor in London’s West End and is an accomplished musician. He’s got more than 20 years of diving experience and is one of the world’s leading technical diving instructors. A qualified recompression chamber safety officer, he managed the logistics and safety divers for Tanya Streeter’s world-record free dive to 525 feet (160 meters). Recently, he was an actor, screenwriter, stunt diver, and dive coordinator for the feature film Sanctum. If you want to know everything there is to know about a “rebreather” and how to use it safely to explore the ocean, you pick up the phone and call John Garvin.

And that’s what Jim Cameron did when he needed a project manager for the life-support system for his new sub. As the DEEPSEA CHALLENGER came together, John also took on the responsibility of positioning and testing every component inside the crew sphere. “It was a team effort,” he says, “We started with the harsh constraint that the interior of the sphere was only 43 inches in diameter. Think of a man crouched inside a refrigerator and the engineering challenge of making sure he has everything he needs to survive and operate a 12-ton sub at full ocean depth. ‘Everything’ includes breathing gases, tablet computer, compass, sonar, manipulator, fire extinguisher, VHF radio, circuit breakers, emergency batteries, emergency breathing system and controls for the batteries, thrusters, trim shot, cameras, and lights. And a red release switch to drop the ascent weights and come up. I now understand what it took to build the Mercury space capsule.”

With the caution of a cave diver squeezing through a choke point, I slowly lowered myself into the combat confines of the pilot sphere. I went in feet first, turned around, grabbed a small handle, bent my body forward, moved my legs around an obstacle, ducked my head under two video screens and leaned backwards until I was lying on my back with the top of my head hard against the pressure hull. My arms, legs, and chest were inches away from rows of screens, controllers, levers, and switches.

I ran my eyes over the claustrophobic curves of the interior and it became clear that the sub worked because John and his team spent tens of thousands of hours making the pilot sphere habitable, operational, and safe. It also became clear that Jim didn’t dive the sub; he wore it.

I’d spent hours inside the simulator in Sydney, but this was the real deal, the pilot’s flight seat, a place of processed oxygen, scrubbed carbon dioxide, and working sweat. This was where Jim compressed his fear, controlled his racing heart, and made his epic journey. When the hatch opened, the first thing he did was to reach up and shake John Garvin’s hand in gratitude.

Photograph by Joe MacInnis